Coins with Two Heads

Claims are debatable assertions. They are the heart of argument. Your thesis statement is always a claim of one kind or another. Without claims, there are no essays worthy of calling essays. You write a clear and vivid thesis statement (your claim) precisely to call your reader’s attention to the assertion you wish to debate. You plan to win the debate, of course, by providing evidence to support your claim, and reasoning to draw the appropriate inferences from that support and, in some cases, to recommend action that should be taken because of the claim you have proved.

Factual Claims are your evidence; your interpretations of the evidence are Inferential Claims, you base your recommendations for action on Judgment Claims.

CLAIMS OF FACT

Ordinarily, we don’t debate claims of fact, but we can refute them on the basis of accuracy.

- A coin is as likely to turn up heads as tails.

- Over time, a single coin will turn up heads as often as it turns up tails.

INFERENTIAL CLAIMS

Inferential claims might sound like facts, but they’re actually opinions based on facts or conclusions drawn from an analysis of facts. Every inferential claim can be argued, because every inferential claim is in fact an argument and, what’s more, it may contain countless smaller steps that can also be argued.

- After ten heads in a row, tails is more likely on the next flip.

- Every flip after the first is influenced by prior flips.

- After the first flip, no flip is fifty-fifty.

JUDGMENT CLAIMS

Judgment claims are opinions based on values, beliefs or philosophical concepts. They expand inferences into prescriptive statements about what should or should not happen, once we accept that the inferences are true.

- No coin toss after the first should ever be used to determine questions of consequence.

Notice how the ground has changed under this argument as it progressed from facts to judgments. The fact that a coin is as likely to show heads as tails is challenged by a reasonable inference that once it has flipped heads ten times in a row, it’s almost certain to flip tails next, to an equally reasonable inference that if ten flips influence the next flip, each flip must influence the next one-tenth as much, to a conclusion that flips after the first are not wholly random, followed by the judgment that if not wholly random, coin flips shouldn’t be used to produce the sort of randomness we consider fair.

Mathematicians tell us that even after ten head flips, a coin is still just as likely to turn up heads as tails, and we may be able to rationally agree, but we don’t listen to arguments wholly rationally, and it sure seems more likely we’ll see a tail next.

Inferences, therefore, are the dangerous part of argument.

The video below makes a straightforward argument in favor of harvesting the organs of death row inmates following their execution for transplantation into patients who will die without new organs. (It’s a little grisly, but if you can watch Saw or Dexter, you’ll be fine.) Listen for the facts, the inferences, and the judgments.

Next up comes a story from the Wall Street Journal that reports China will soon stop harvesting organs from its executed prisoners. This is not an opinion argument, but watch out for inferences and judgments anyway. Here’s the entire text:

China to Stop Harvesting Inmate Organs

By LAURIE BURKITT

BEIJING—China officials plan to phase out organ harvesting of death-row inmates, a move to overhaul a transplant system that has for years relied on prisoners and organ traffickers to serve those in need of transplants.

Huang Jiefu, China’s vice minister of health, said on Thursday that Chinese officials plan to abolish the practice within the next five years and to create a national organ-donation system, according to a report from the state-run Xinhua news agency.

“The pledge to abolish organ donations from condemned prisoners represents the resolve of the government,” Xinhua quoted Mr. Huang as saying. The Ministry of Health didn’t respond to requests to comment.

Officials in the world’s most populous country have conceded that China has depended for years on executed prisoners as its main source of organ supply for ailing citizens. Human-rights groups say the harvesting is often forced and influences the pace of China’s executions. Mr. Huang has been quoted in state media reports as saying that the rights of death-row prisoners have been fully respected and that the state asks for written consent prior to donation.

Due in part to traditional beliefs and distrust of the medical system, voluntary donations are rare in China, where the need for organs far exceeds the supply. An estimated 1.5 million people in China are in need of organ transplants annually, while only 10,000 receive them, according to government statistics. In the U.S. in 2009, 14,632 organs were donated, while the transplant wait list had 104,898 patients, according to data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

An estimated 65% of China’s organ donations come from prisoners, according to 2009 data, the most recent available, from human-rights advocacy organization Amnesty International.

Chinese officials have said relying on organs from prisoners isn’t ideal. Human-rights advocates doubt that China will be able to phase out the system entirely, because of the heavy dependence on it. They say that the government’s efforts to educate the public on organ donation have been inadequate. “Officials repeatedly make announcements every few years, but they don’t appear to have a solid plan in place,” said Sarah Schafer, a Hong Kong-based China researcher for Amnesty International.

The dependence on prisoners for their organs influences the timing of executions in China and in many cases bars inmates from the ability to appeal their death sentences, she said. While such appeals are rare in China, prisoners sometimes get a reprieve on death sentences, enabling them to escape execution.

Xinhua cited Mr. Huang as saying that infection rates for prisoners’ organs are typically high, causing a lower long-term survival rate for Chinese with transplanted organs than for people in other countries.

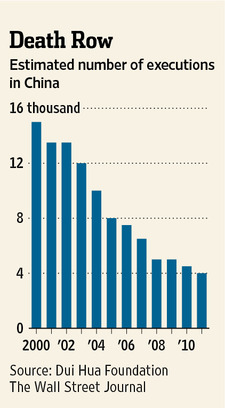

China’s previous efforts to stem the practice have faltered, Ms. Schafer said, citing a goal set five years ago by Chinese officials to reduce reliance on prisoner organs by 2012. Xinhua reported that the number of organ donations from inmates has decreased in recent years due to a more prudent use of the death penalty, though it didn’t supply specifics.

China doesn’t publicly report execution figures, but San Francisco-based human-rights group Dui Hua Foundation estimates that 4,000 prisoners were executed in 2011. China’s death penalty rates are higher than any other country in the world, according to Dui Hua figures. Amnesty International no longer reports execution data from China, but believes the figure is “in the thousands.”

By comparison, there were 43 executions in the U.S. in 2011, according to Washington nonprofit organization Death Penalty Information Center.

Some Chinese patients awaiting transplants say abolishing inmate donations will be akin to a death sentence for them, according to a report published in the medical journal Lancet in 2011. The report said the number of patients requiring transplants is growing due to the rise in chronic and noncommunicable diseases in China.

The Ministry of Health and the Red Cross launched a voluntary organ donation program beginning in 2010 that has been tried out in 16 of China’s mainland cities and provinces. Since March 2010 the program has resulted in the donation of 546 major organs, according to a statement from the Red Cross.

China’s lack of available organs has also created a black market for ailing patients wealthy enough to afford them. State-owned China Daily has reported that kidneys purchased from organ traffickers can cost about $29,000.

Chinese officials banned organ trafficking in 2007, restricting all living organ donations to spouses, blood relatives, and people with close family ties.

—Yang Jie contributed to this article.

Presumed Consent

Although the word compulsory is usually used in arguments of this sort, the more accurate term in most jurisdictions is “presumed consent.” In countries where organ donation is automatic upon death, people are given an opportunity to “opt out” of the obligation by registering their refusal to donate organs, just as in this country we register our willingness to donate ours. The burden shifts to those who oppose donation, but it’s not much of a burden to make their wishes officially known.

Should Donation be Compulsory?

Now let’s hear from a young man whose life was saved by a double lung transplant. Surely he’s in favor of donation.

http://www.4thought.tv/themes/should-organ-donation-be-made-compulsory/oli-lewington?autoplay=true

Don’t Give Your Heart Away

And finally, here’s a very thorough explanation of the mechanics of “non-paired” organ donation (the donations which, like the heart, are not part of a pair of organs) from an ardent opponent of donation who recommends carrying an “opt-out” card to avoid the possibility of becoming a donor.